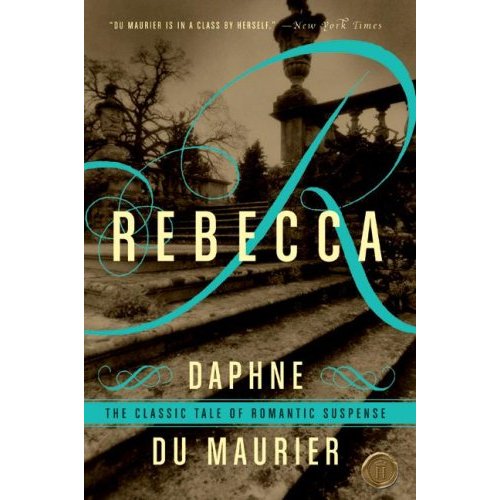

The classic novel Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier is an example of particular style and daring told from the nameless heroine's POV in the late 1930s and early '40s. With a dark and foreboding presence throughout the novel, at first the reader assumes it's from the moody widower Maximilian de Winter but really it's from his dead wife's taunting, haunting spirit penetrating the estate of Manderley and all who knew her.

The young heroine recalls her meeting of the much older Maxim as the story begins with her reflection of her time as the employee of a brash and unattractive woman who travels to all the European hotspots to meet celebrities and those patrons of high society. The heroine is no more than a shadow to the boisterous woman who may or may not know what a bore she is with her pompous, self-indulgent picture of herself.

To the heroine's surprise, Mr. de Winter shows an interest in her during their stay in Monte Carlo, and they steal time together until her employer suddenly desires to join her daughter in New York. The heroine is crushed that she must leave this new romance and the man with whom she believes she's falling in love. When he proposes to her in a completely clinical manner, she accepts, stunning her employer who leaves with a warning that she mustn't think he truly loves her.

Her insecurities abound after a whirlwind marriage and honeymoon in Italy when they return to Manderley, his ancestral estate. The evidence and memory of Rebecca, his former wife who's been dead for almost a year, is current and follows the young bride's every actions and words. Her inferiority is accentuated daily, particularly by the head housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, who she learns adored Rebecca and has no love or respect for the intrusion of the new Mrs. de Winter.

Maxim de Winter does little to encourage his bride, leaving her to her elaborate imagination concerning his former wife and their relationship. Her interpretations of his actions mirror those of a love-struck schoolgirl at times accentuating her innocence in life and matters of love as well as her divided and conflicted emotions. Mrs. Danvers intimidates her at every opportunity, and references to what Rebecca would've done or did plague the heroine. Seeing her handwriting with her sweeping R and grandiose style adds to her ill feelings and discomfort about herself and her doubts about Maxim's love.

Everything builds to incorporate the heroine's ongoing awkward position at Manderley and culminates when she takes Mrs. Danvers' ill-advised suggestion for a costume to wear at the great Manderley Ball which the local people clamored for and which Mr. de Winter grudgingly agrees to host if his agent (estate manager) will take care of the planning. The result is stunning.

When Maxim finally breaks down and reveals the truth to his young wife, it's fascinating to read. The transformation this truth produces does not go unnoticed by either of them. After much ado, fearful expectations and dread, a conclusion is reached. The strange and startling abrupt ending thrusts the story back full circle to the first chapter and a half which could have fit nicely into a prologue or prelude but worked seamlessly as chapters.

Daphne Du Maurier's Rebecca is an amazing tale of loneliness, jealousy, pretense, devotion, cunning, and malice. One might even call it an elongated coming of age story. With a detailed look at the fears and insights of a young bride facing the entrenched memories of a larger than life woman who preceded her, Rebecca shows the intertwining of darkness and light, truth and fantasy. Well worth the repeat read.

Father, you've always given to each one. Many never see it, but it's there. Always. Thank you. In the Name of Jesus, Amen.

Leave a reply to Nicole Petrino-Salter Cancel reply